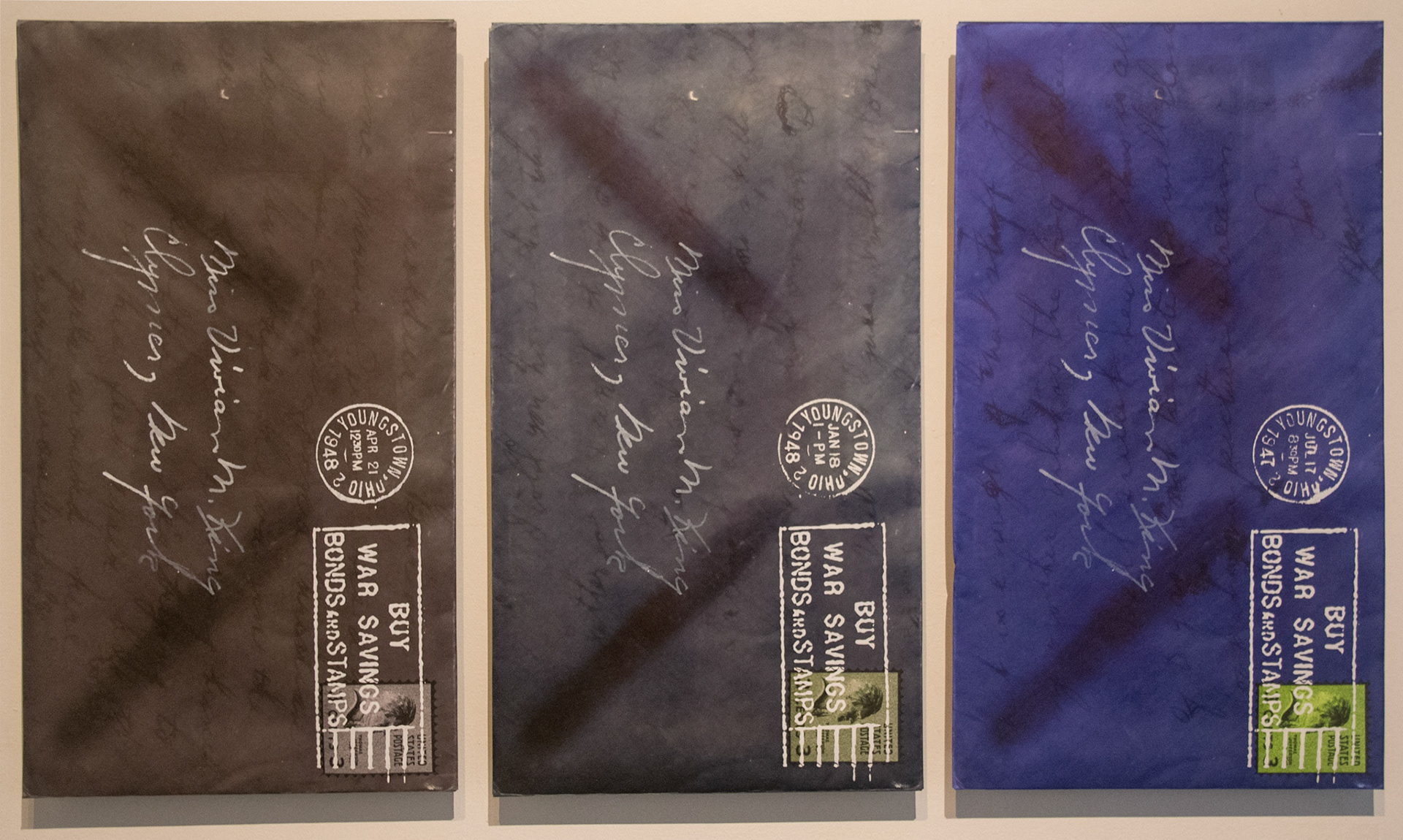

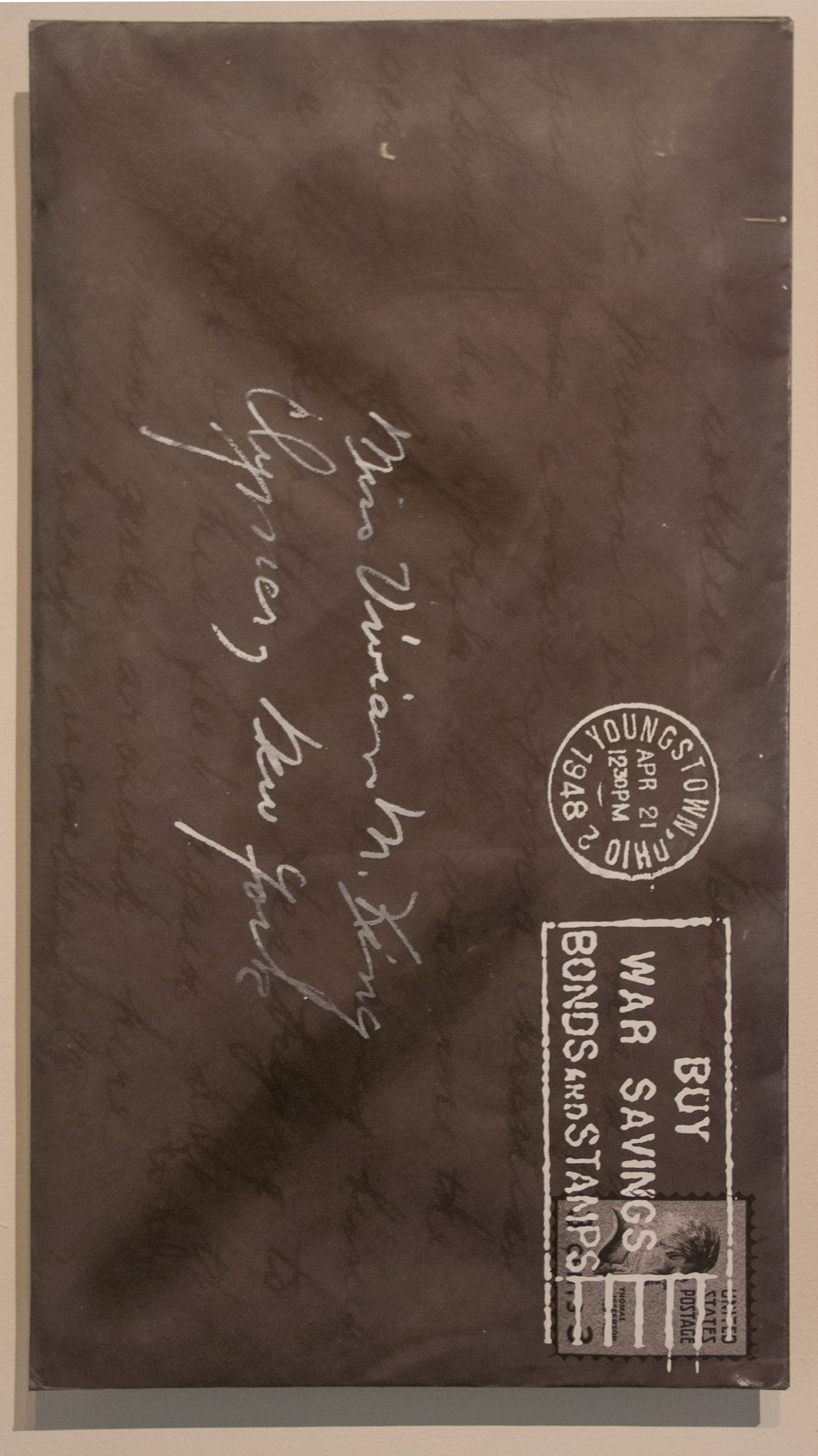

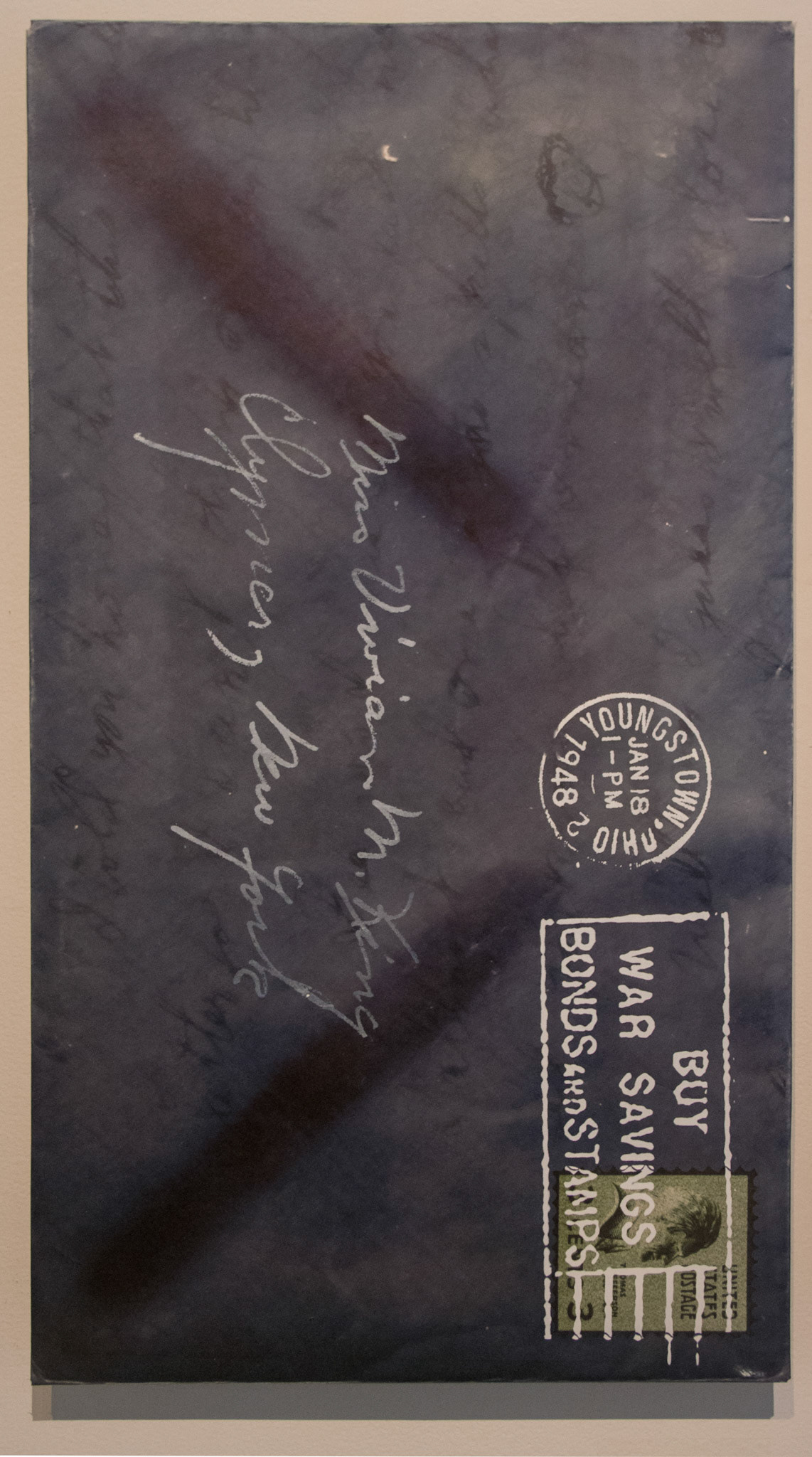

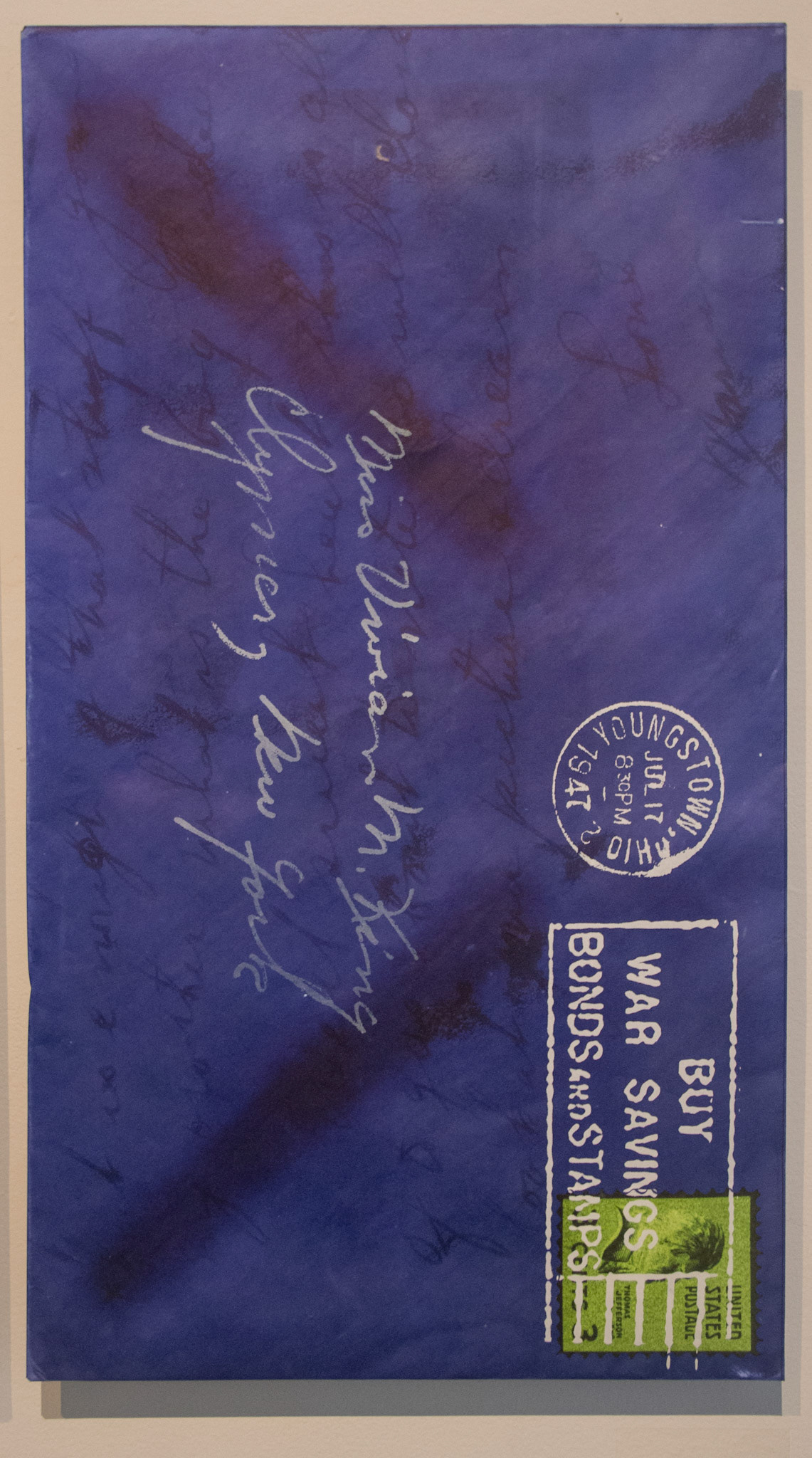

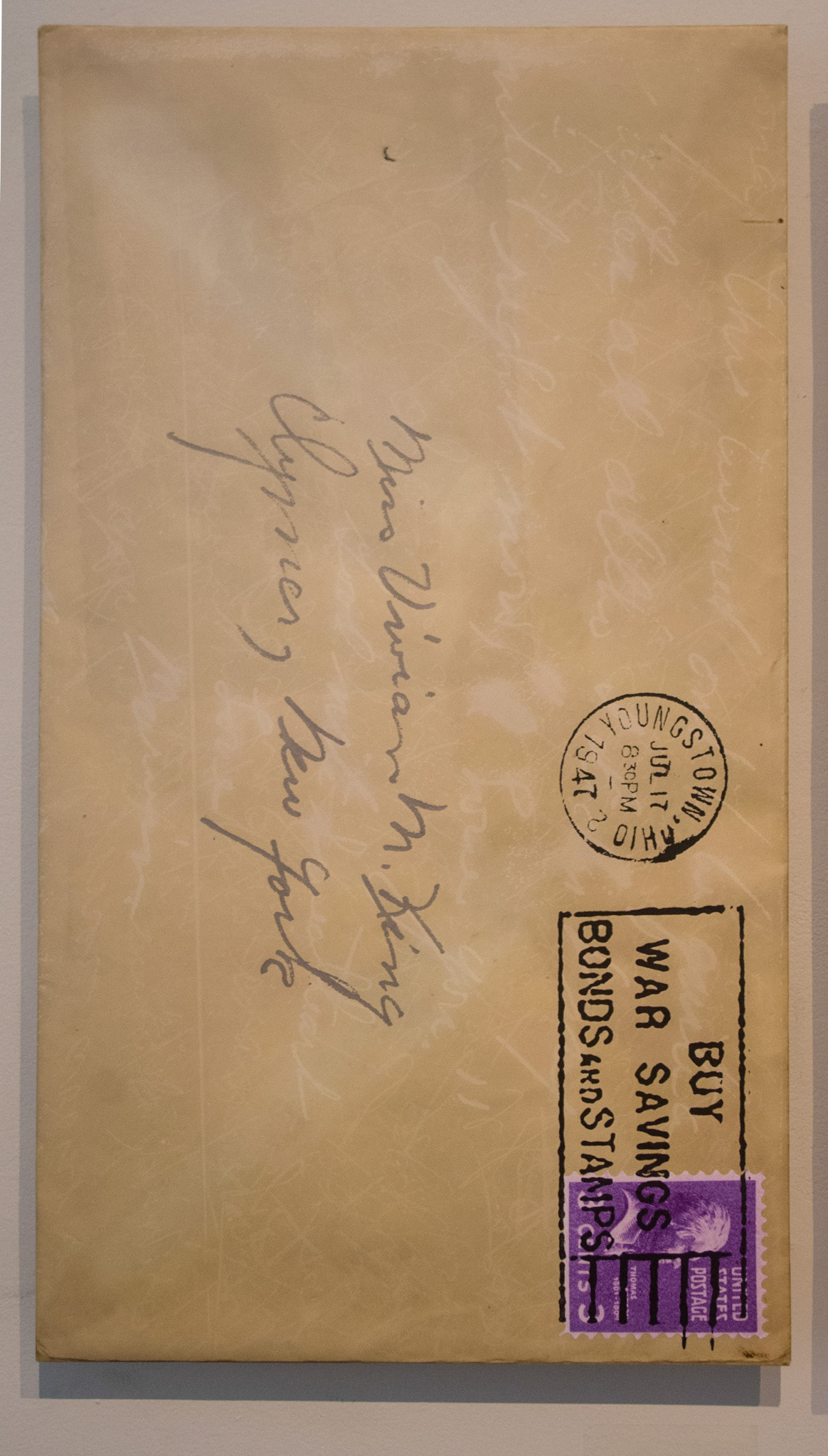

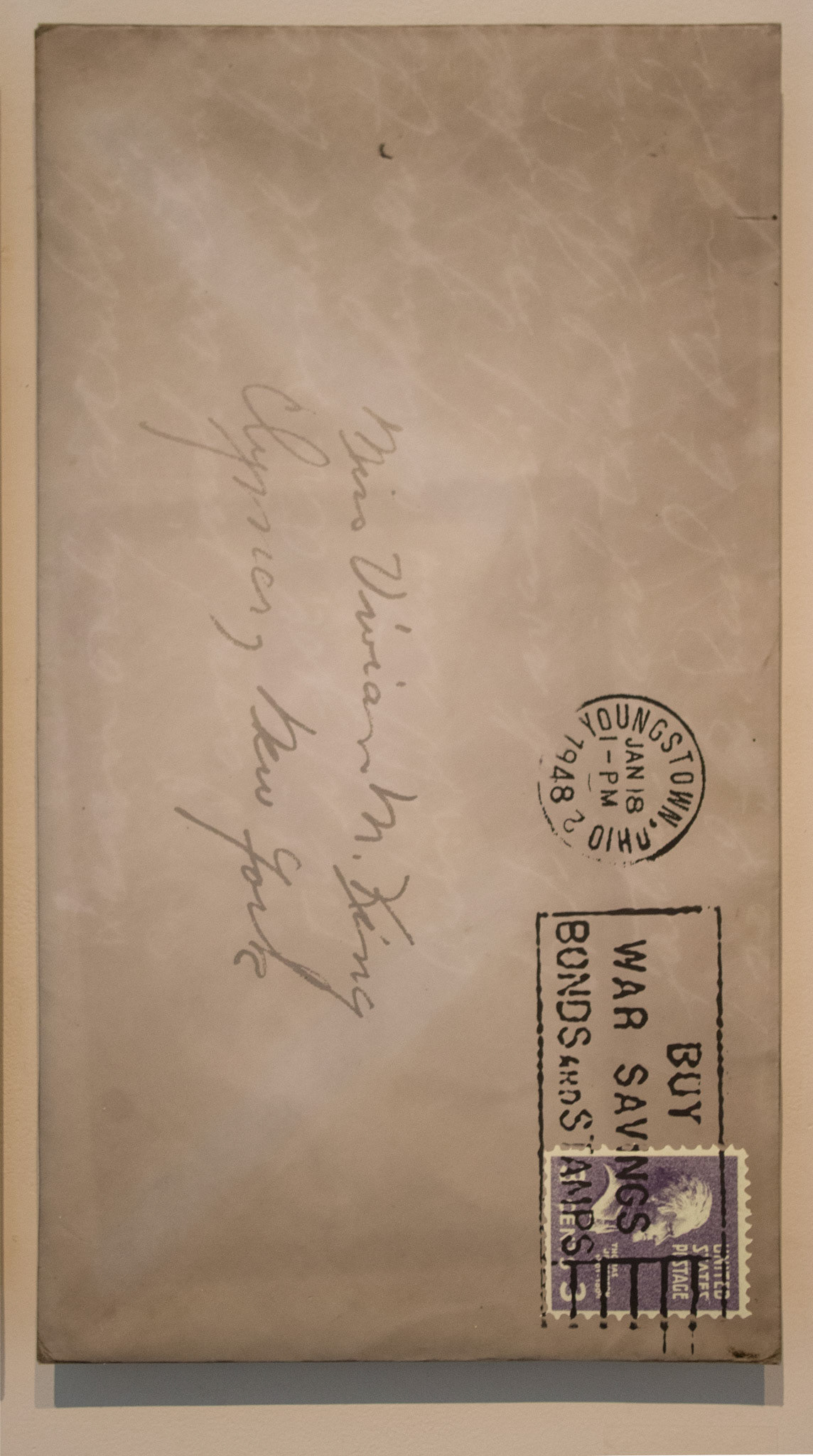

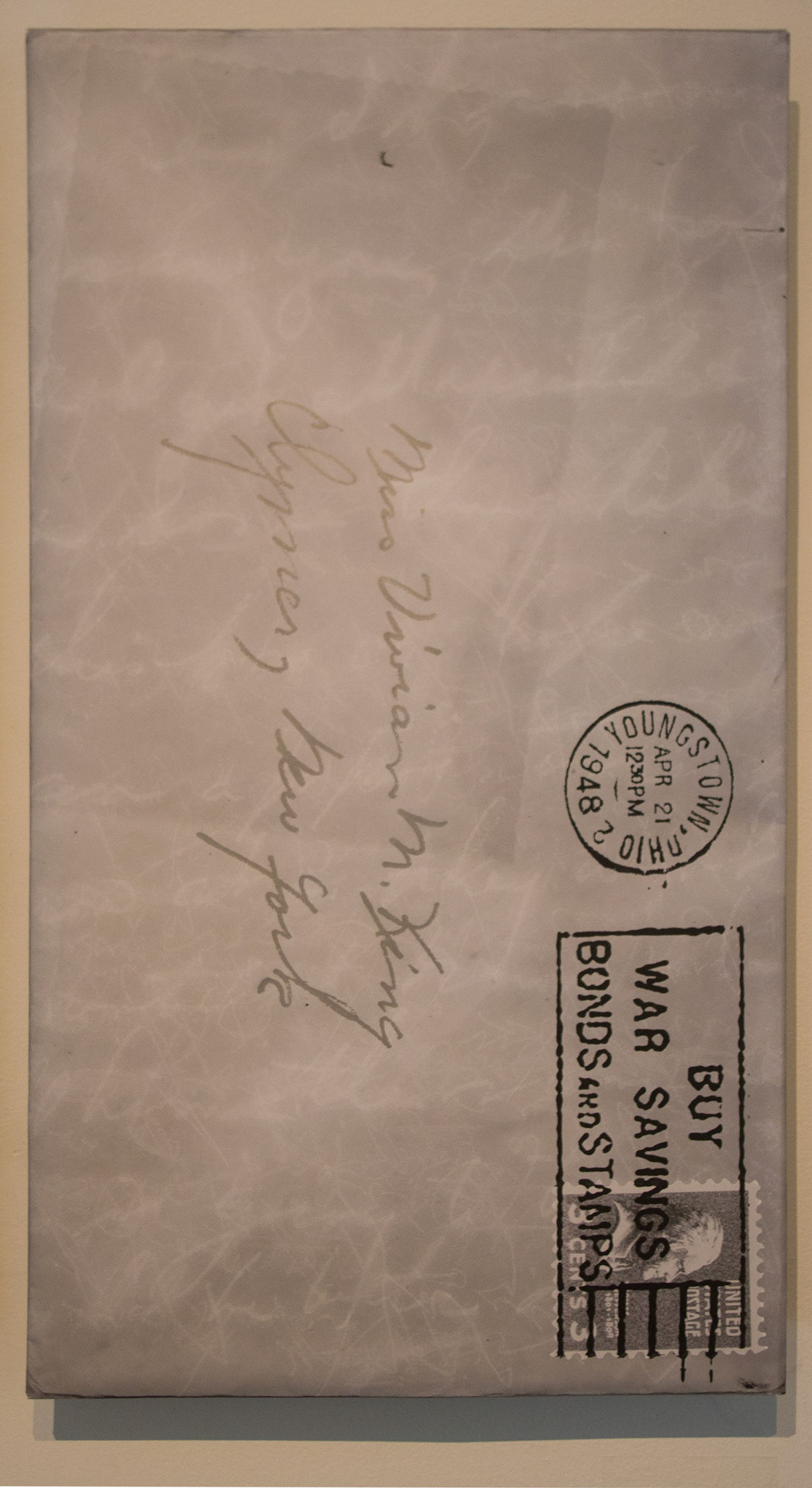

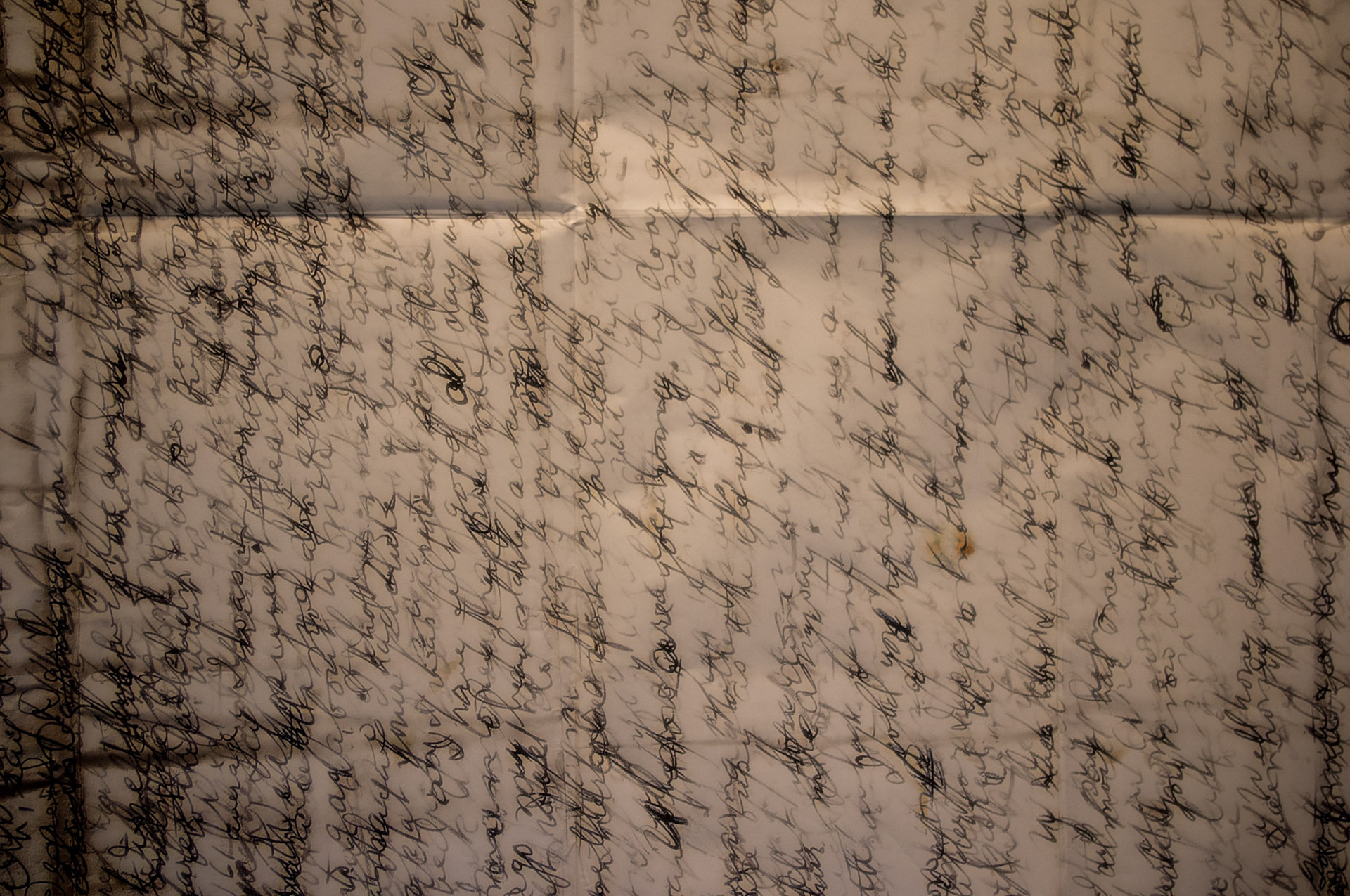

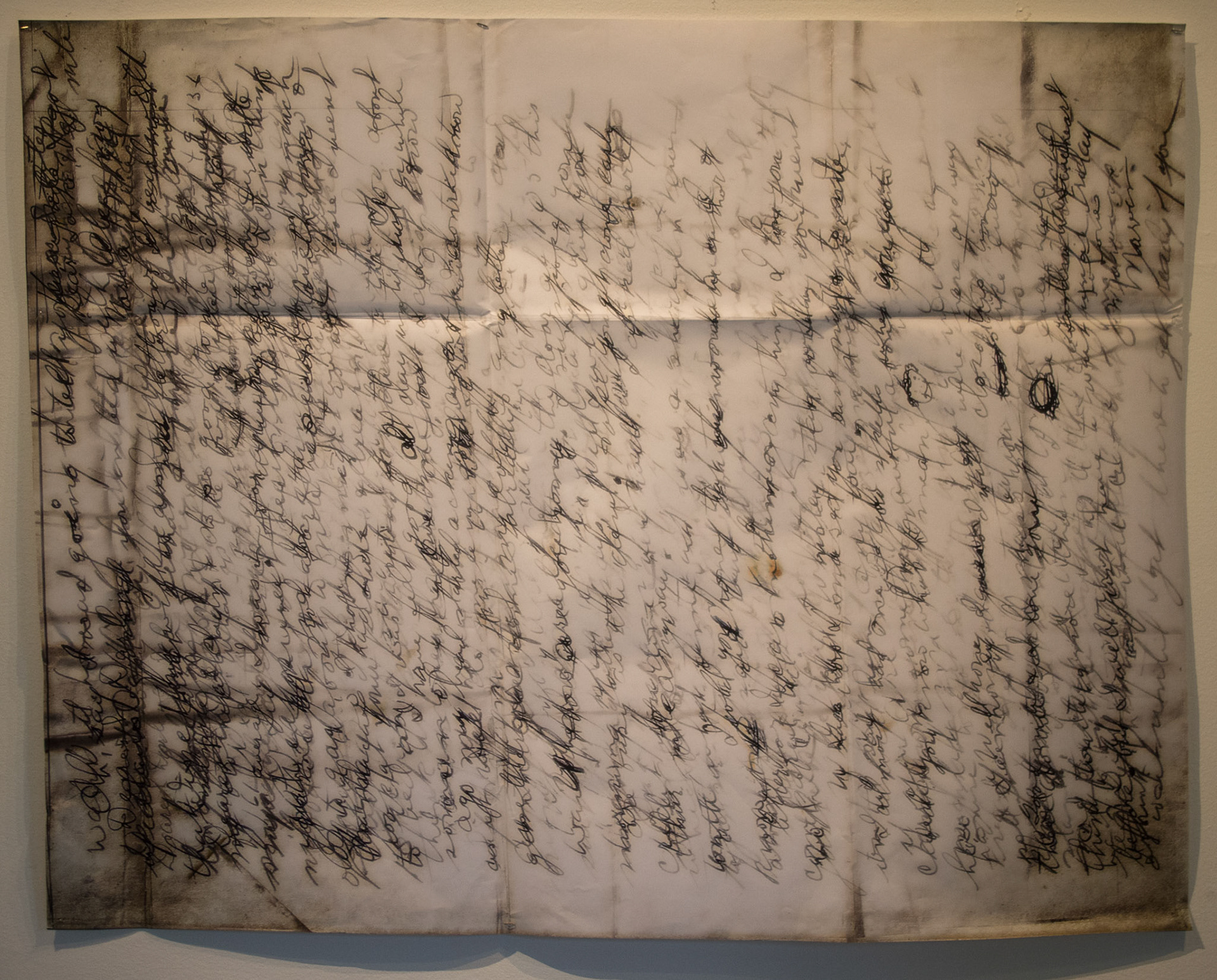

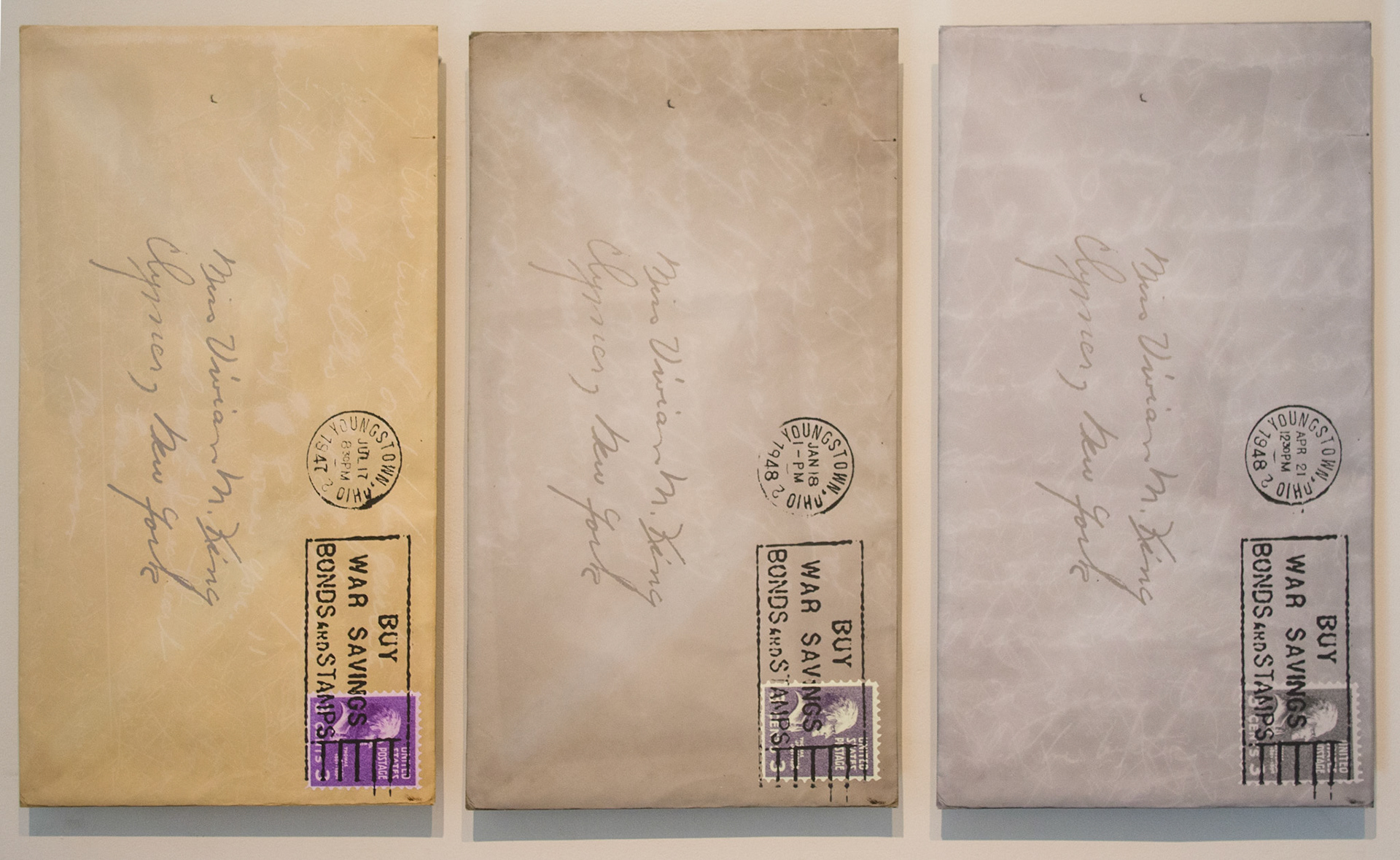

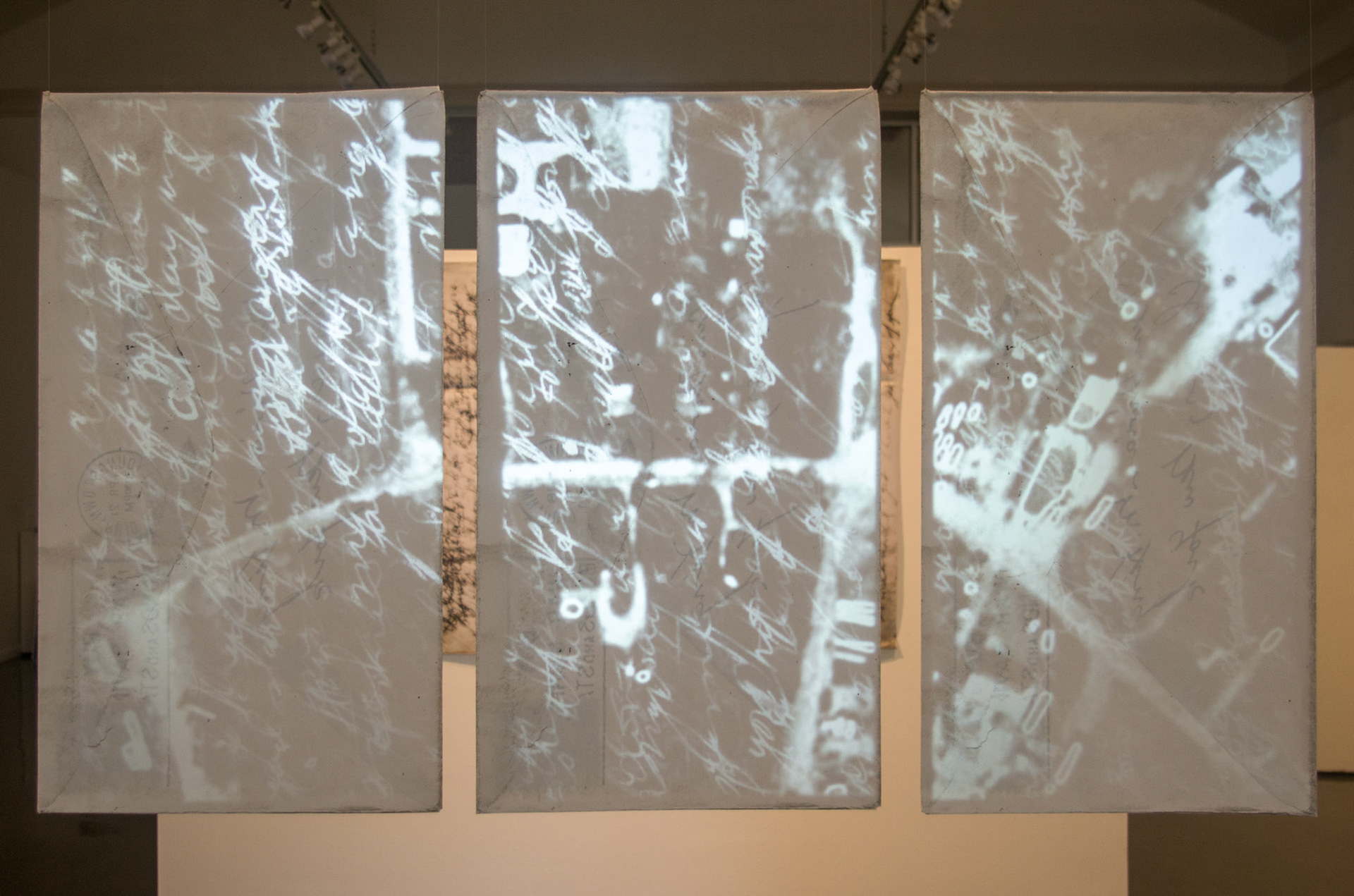

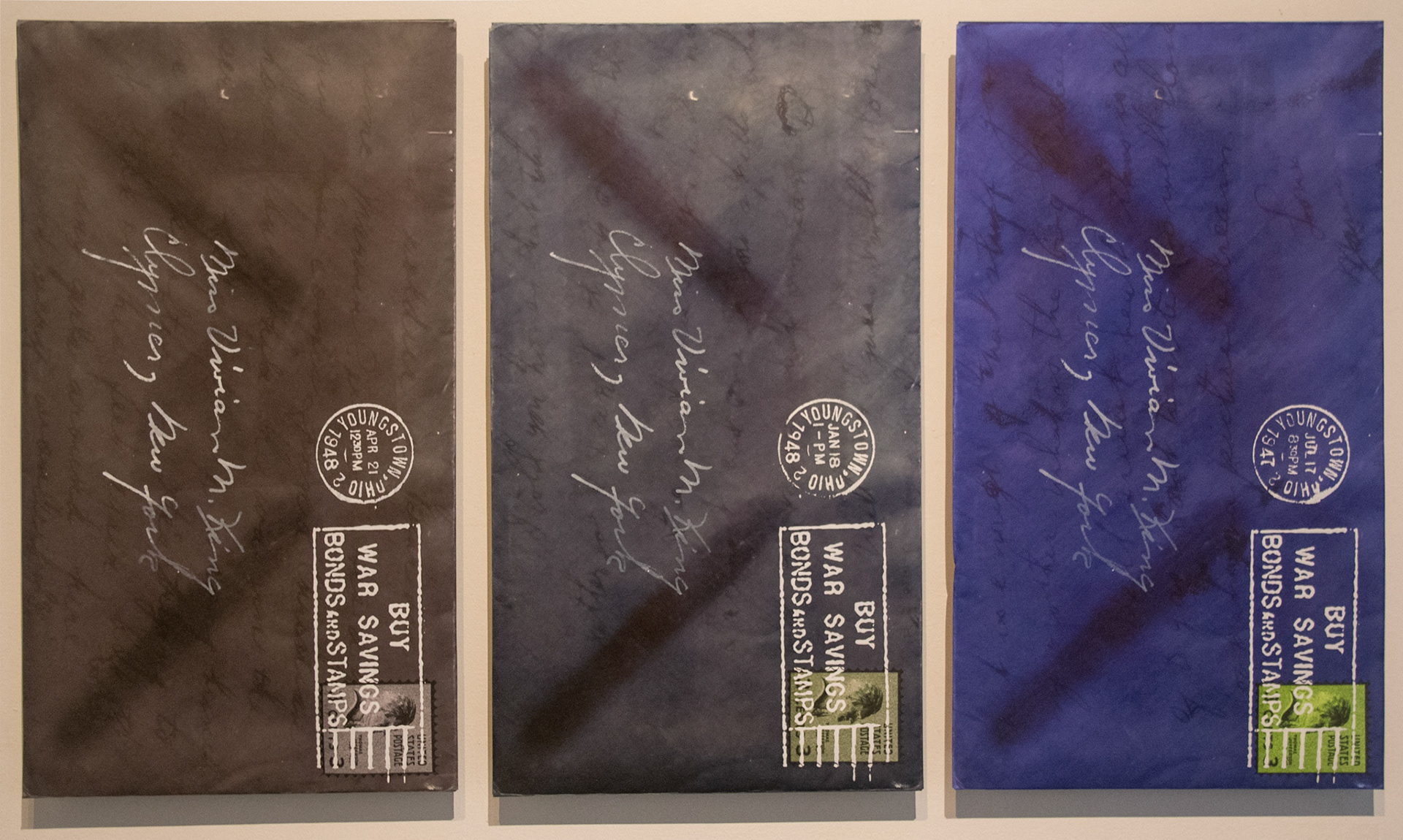

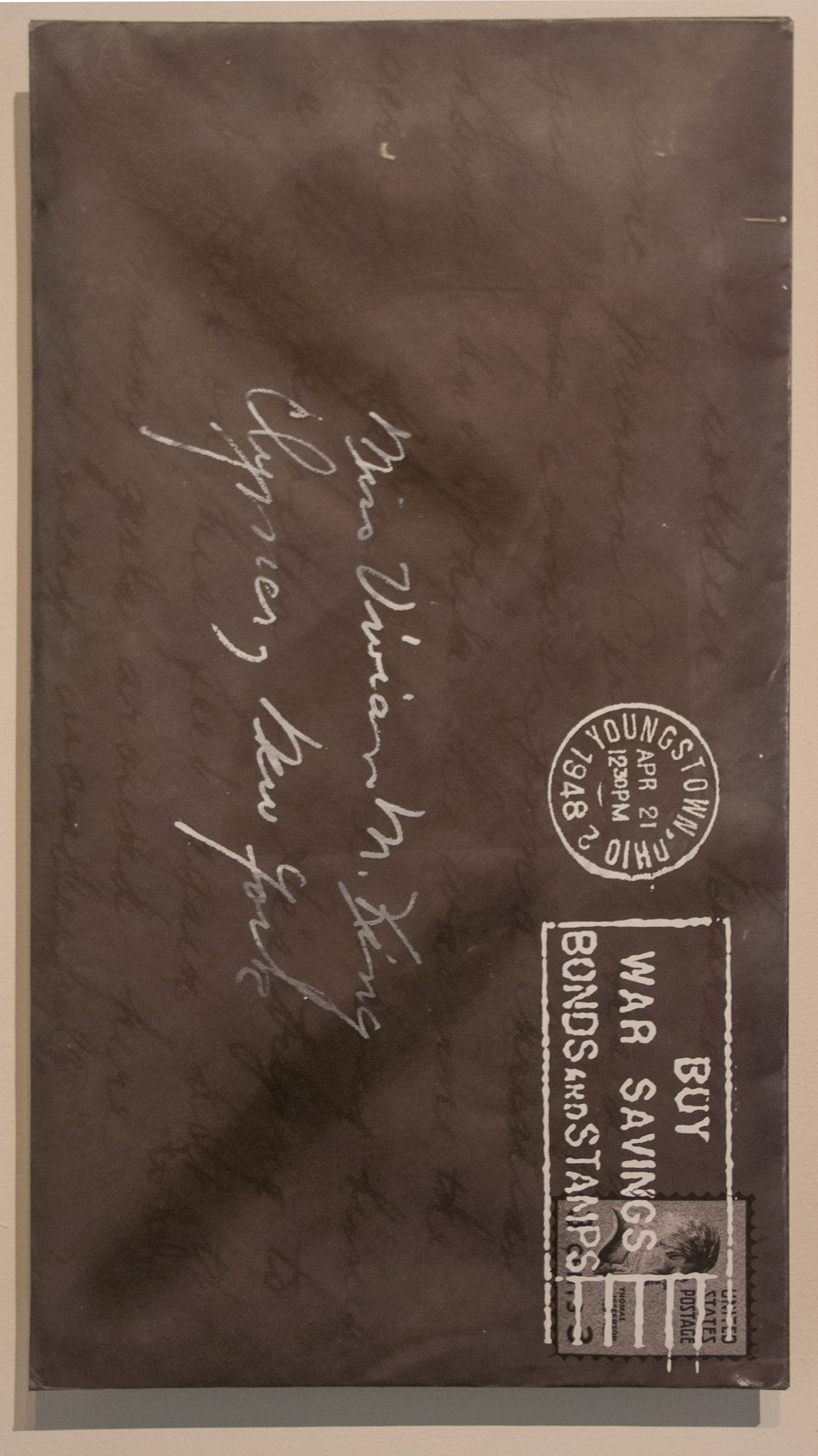

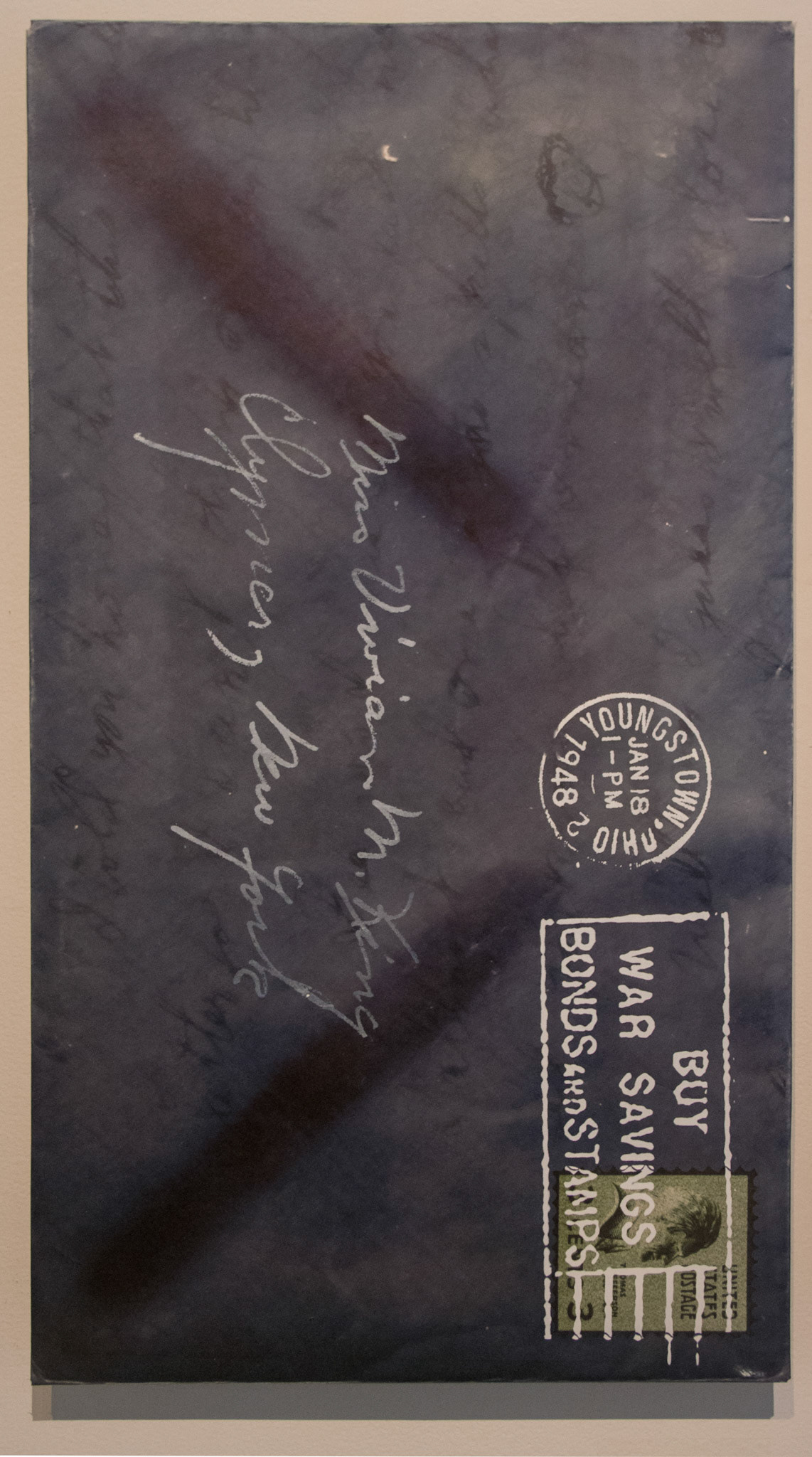

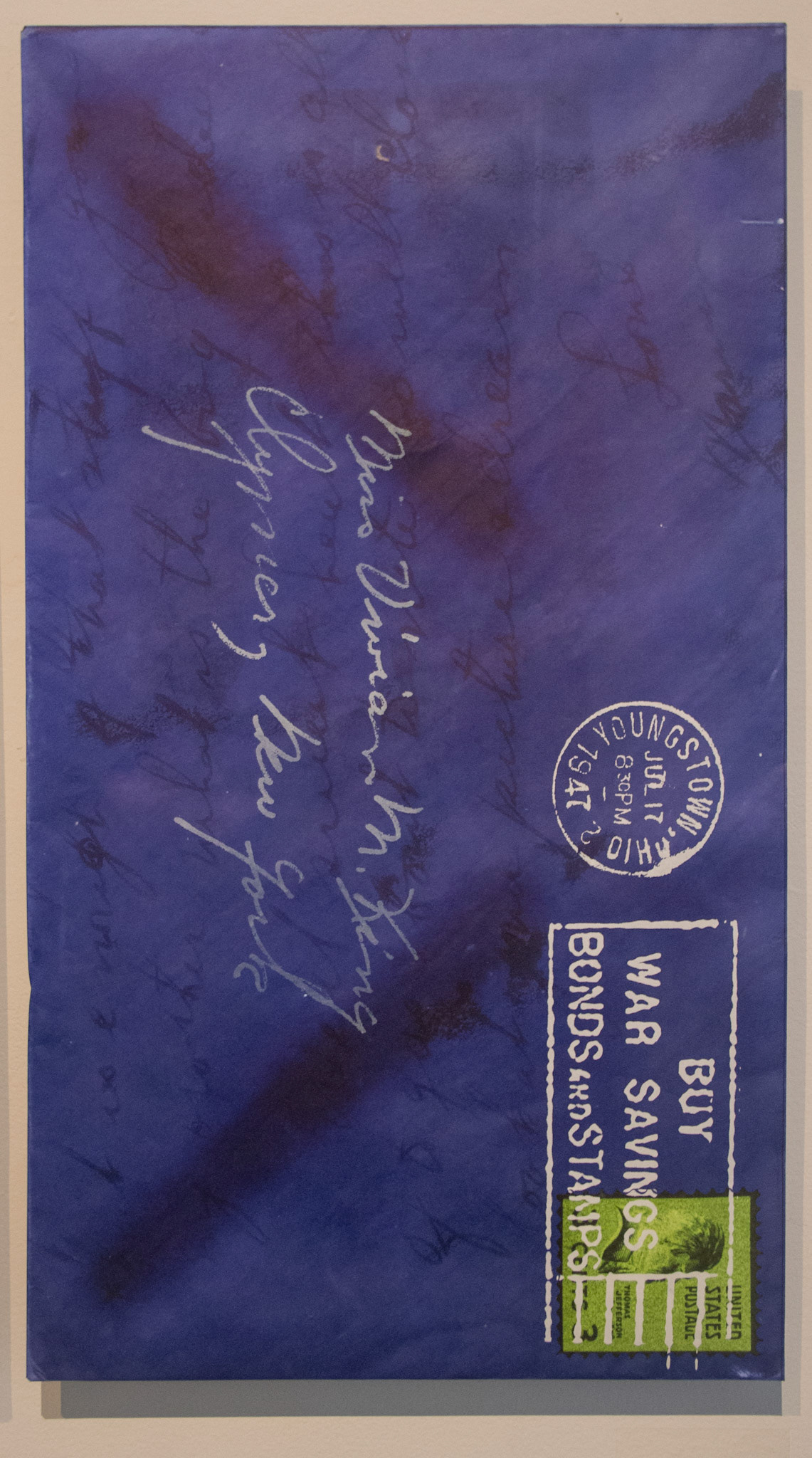

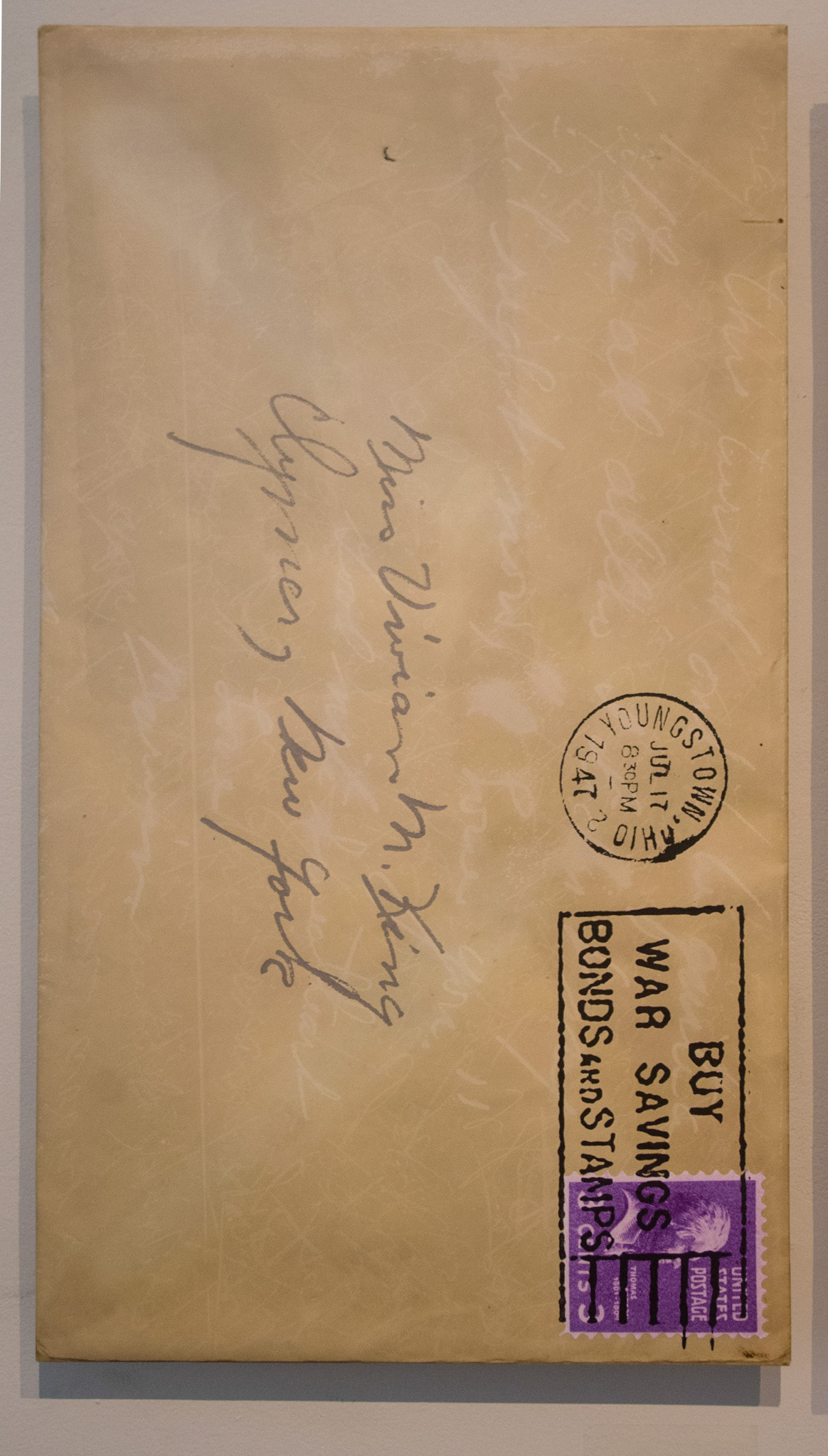

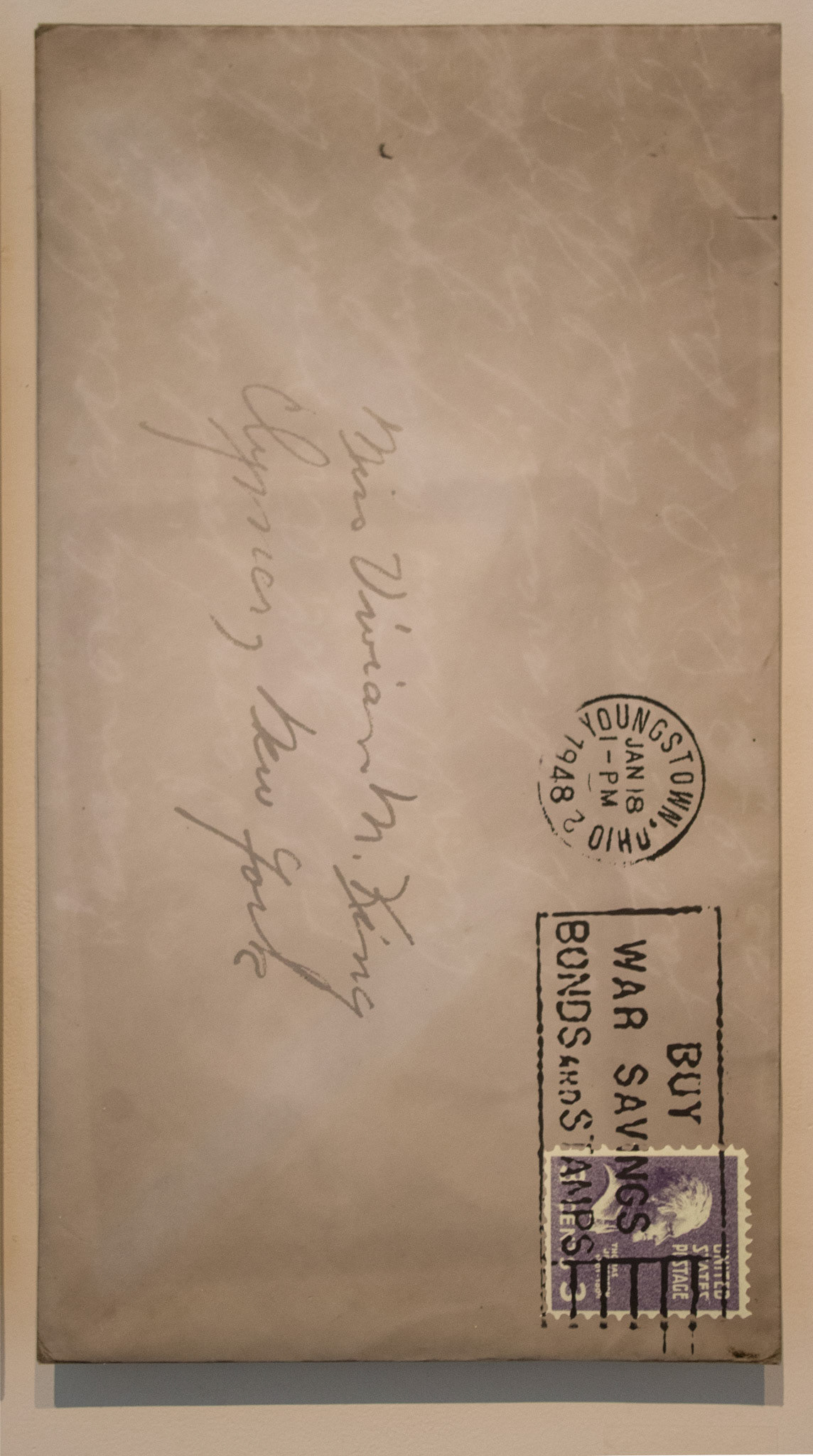

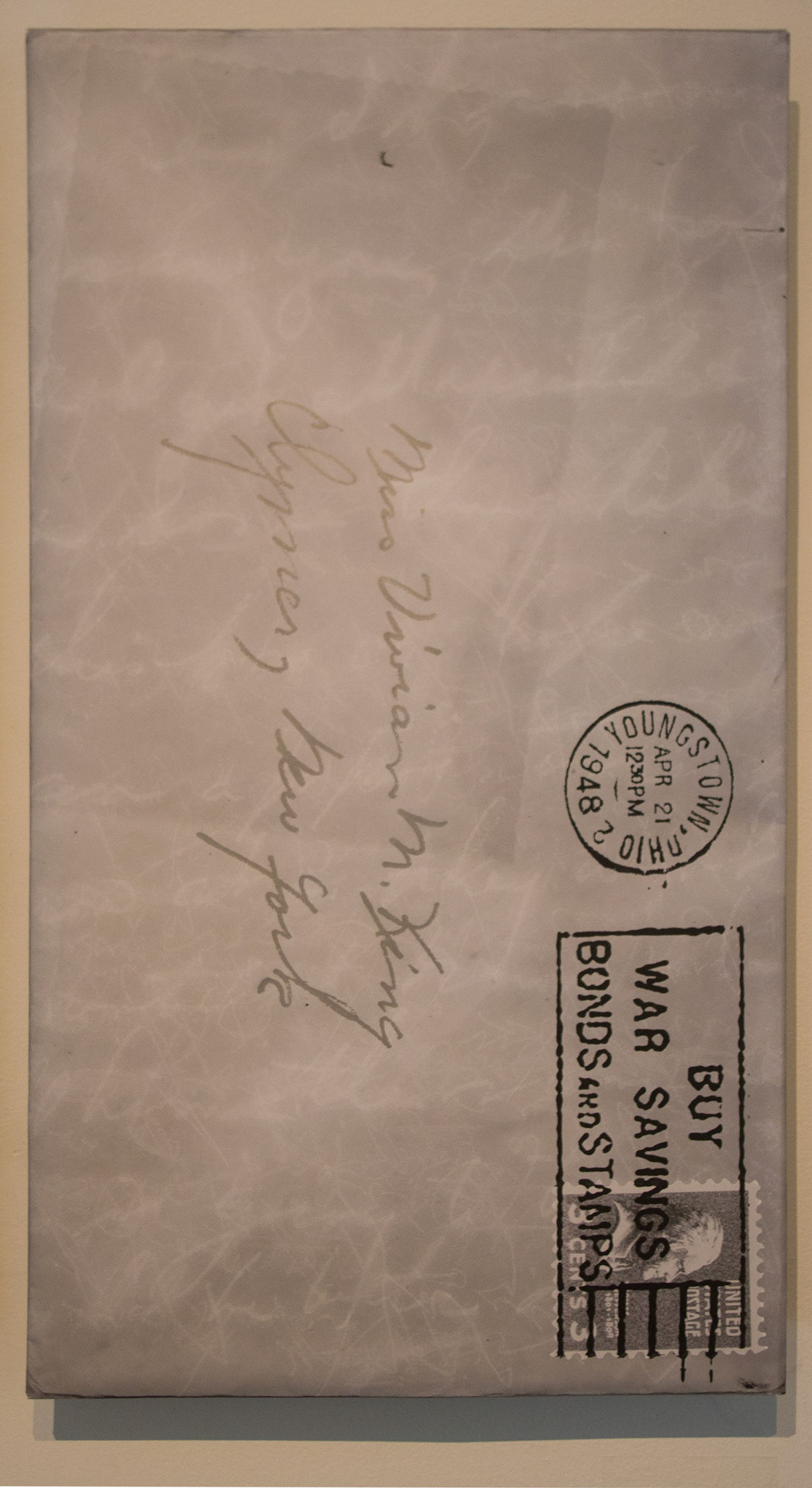

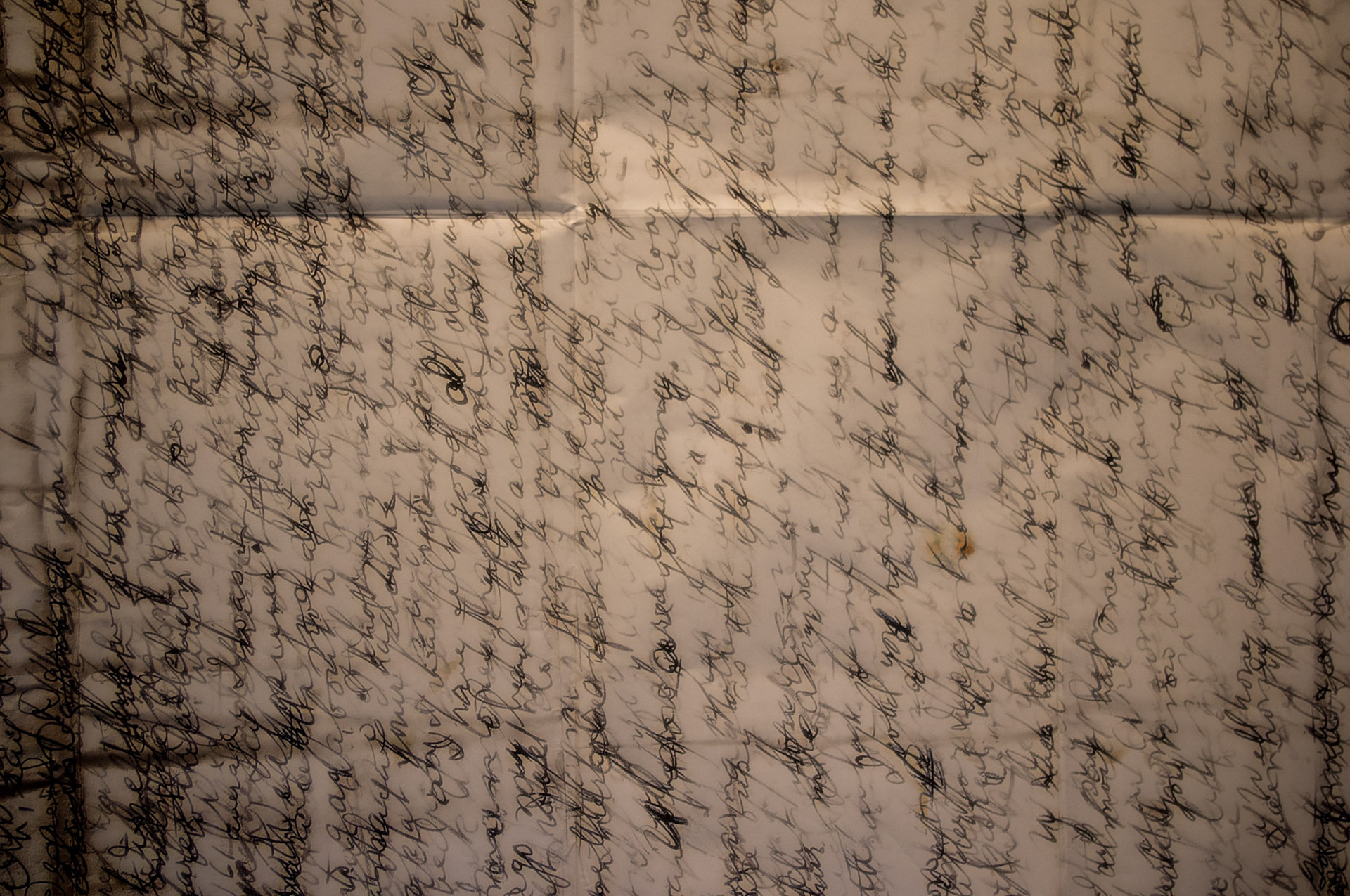

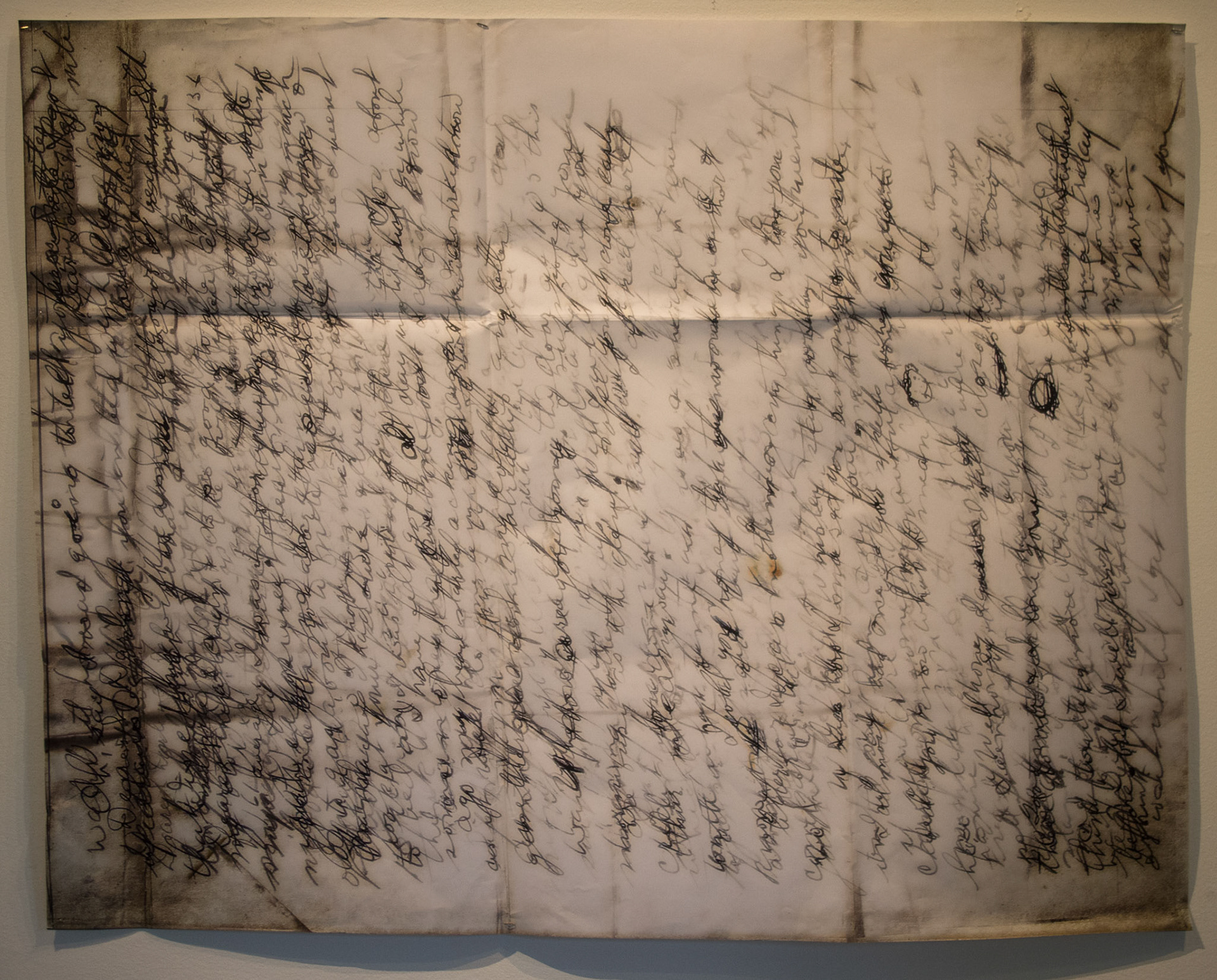

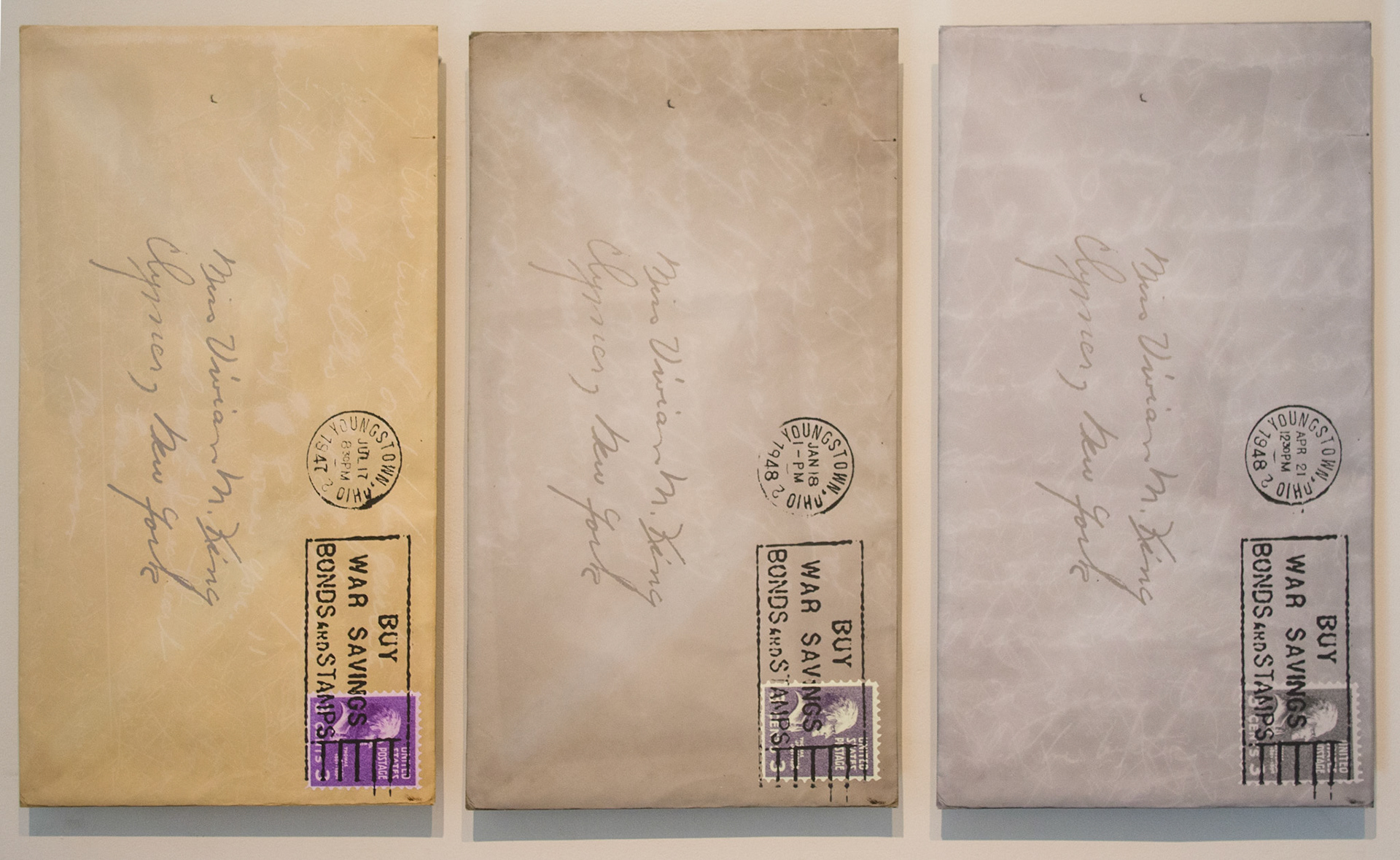

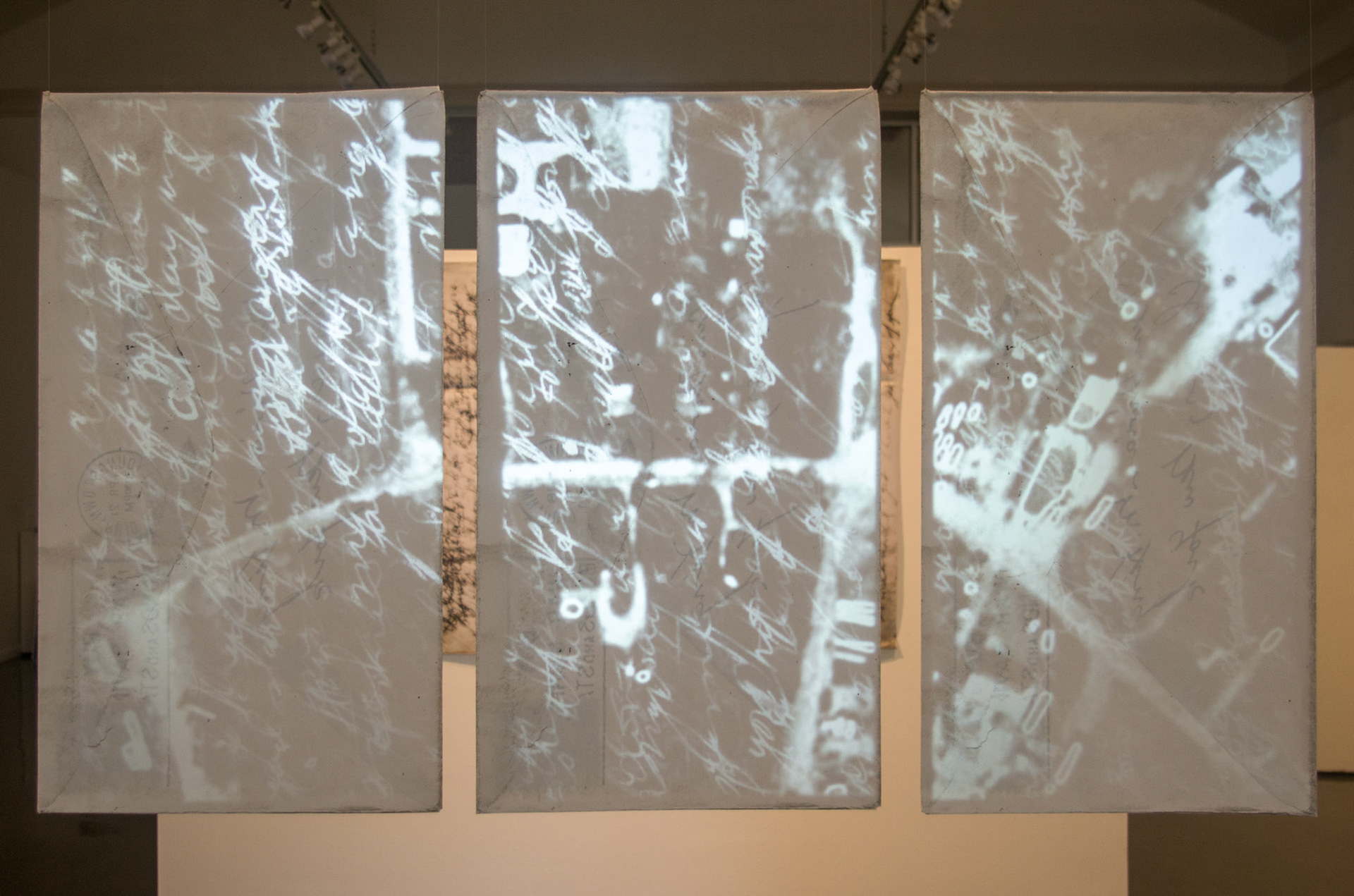

The envelope is of little significance…until it is filled and addressed. An invitation on a date, a couple’s first tax return, the announcement of a baby shower; not only do they provide cover to correspondence, but they also become vessels of life experience. Digital disruption may relegate them to the junk pile, but as they are relied upon less, they come to carry more: a personal touch. Virginia Jackson, writing on Emily Dickinson, describes the written address as conjuring “a presence more intimate than a whisper.” Dickinson herself recorded poetry on envelope covers, exemplifying how the object becomes involved beyond utilitarian purpose. The envelope turns into a proxy: one of many, easy to lose, fragile…but a connection to whom from which it came. In Letters to Vivian, the digital is a means of preservation rather than disruption. Archiving an ephemeral correspondence my grandfather wrote to my grandmother as a young man is an opportunity to know the person more than time allowed. Through network access, relatives can participate in understanding a common point of origin. The collection serves as source material for compositions that investigate the role of the object in these interactions. Enlarging the envelopes makes a memorial out of the mundane, while color and tonal manipulations explore turning the inside out. A video projection permits the viewer to see through the cover to the contents inside, and an accompanying sound collage lends voice to the handwritten. If, to quote Virginia Woolf, life is a “semitransparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness,” then the work carefully unfolds the sender to let the viewer see within. This glimpse into a life history that is not their own offers evidence of the collective memory of all humankind.